Vol. #14 July 2020

July 17, 2020

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 health professionals have raised a need for a heightened focus on mental health as individuals continue to experience isolation, financial hardship, and many other direct and indirect consequences from the events in 2020. In a recent advisory report from the Massachusetts Association for Mental Health, Dr. Danna Mauch, Ph.D. advises for the state to take steps to “mitigate morbidity and mortality associated with post COVID-19 behavioral health” (1). The report cites recent data measuring the increased volumes of traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and substance use. In April, 45% of Americans had already reported the pandemic had impacted their mental health. Findings from the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute (MMHPI) and the Well Being Trust (WBT) estimate that Massachusetts will experience 160-800 additional deaths from the COVID-19 recession in 2020 and an additional 15,000 to 55,000 extra people will develop a substance use condition (2).

Before COVID-19, making sure there is equitable access to mental health has gone through several strategies. Including, but not limited to making sure culturally competent mental health services existed (3), combating the stigma of mental illness, reducing the financial burden, and doing the work to connect individuals to the existing services. Here in MetroWest, multiple leaders have put forth such strategies to deliver equitable mental health services. Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center includes culturally responsive questions (4) in their patient and staff experience surveys, while Advocates has invested in their marketing and operating environment to be inclusive of all the communities they serve in MetroWest (5). In addition to individual efforts, the collaboration between Advocates, Wayside Youth and Family Support Network, and SMOC has helped our region both reduce financial burden and coordinate a single-entry point of behavioral health providers through the Behavioral Health Partners.

Yet still, outcomes nationally and locally show disparities among those who receive mental health services. There are no consistent service utilization studies but reported outcomes have found non-Hispanic white youth are twice as likely to receive any mental health service when compared to Black/African Americans and Asian American/Pacific Islanders (6), and Latinx adults being half as likely as whites to receive depression care (7). Breaking down access barriers has been the focus of the effort to eliminate health inequalities in the mental health system, but far less has been done to address a system that is not built to be inclusive.

Breakdown of racial disparities in mental health services:

- Service Design: Clinical assessments of trauma have shown to be incompatible with life events and distress symptoms to individuals of color (8). Similarly, often the trauma experienced by people of color is discounted in current clinical assessments of trauma. The MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey consistently found in the 2006-2018 outcomes report, that while Black and Latino youth report more mental health problems, these groups also consistently have lower reports of adult support at school compared with youth in other racial/ethnic groups (9).

- Workforce: The American Psychological Association’s most recent reports of the U.S Psychology Workforce show that while Black/African American professionals have doubled since 2000, they still only represent 4% of the psychology workforce (10). MetroWest has had difficulty recruiting and retaining clinicians who are non-white.

- Leadership: As of 2017, 80% of permanent, interim, or acting department chairs at all U.S. medical schools were white. Of the 155 department chairs for Psychiatry, 119 were reported white (11).

Diversity needs to exist at all levels of mental health services, and in 2020 the opportunity is there. Generation Z, defined as those who are 8-23 years old today, has been declared as the most diverse generation yet with 48% of the generation-defining as a minority (12). More insight from the Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data shows that this generation is also experiencing lower high school dropout rates than the previous Millennial generation and higher numbers of college degree pursuits. At the same time, the oldest of Generation Z are less likely to be in the labor force when compared to Millennials at this age in 2002. In 2002, 72% of Millennials 18- to 21-year-olds reported working in the prior calendar year, compared to the 58% of 18- to 21-year-olds in Generation Z (13).

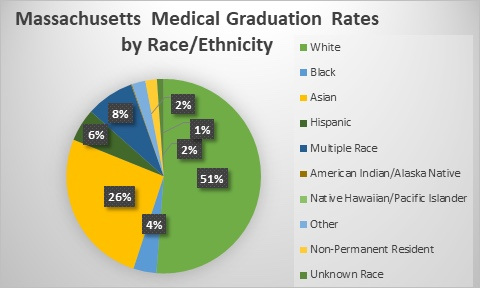

Minority representation in medical school graduates by race/ethnicity is reflected below. In 2018, 48% of medical school graduates in Massachusetts identified as a minority (44% in United States).

Data Source: Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Data and Analysis, Total Graduates by U.S. Medical School and Race and Ethnicity (Alone), 2016-2018

So where do we go from here? No matter our race, we can take action to grow and diversify our systems of mental health services. As a region, we can commit to rise up and mentor young people of color, utilizing services that already exist to diversify the delivery of care, and create roles in leadership that go beyond creating a seat at the table, but acknowledging the voices of people of color. To do that we must:

- Invest in young people of color: The Health Resources and Services Administration, (HRSA) projects that by 2030 Massachusetts will experience a shortage in School Counselors when the unmet need is accounted for. HRSA also projects Massachusetts will barely meet an adequate supply of Psychiatric Physicians, Adult Psychiatrists, and Addiction Counselors (14). Knowing there is a growing demand for care, there is a growing responsibility to support a diverse group of young professionals. As someone that works to reach out to minority populations through programming highlighting career pathways in medicine and other science fields, Inaugural Dean for Diversity and Community Partnership and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Joan Reede, has often criticized the idea that the talent is not there (15). “There is talent out there. We need to be identifying and nurturing these individuals to stay the course.” (16).

- Incorporate what is already out there: InnoPsych, an online national platform created by Dr. Charmain F. Jackman matches patients with therapists of color and helps to support businesses and practices owned by people of color. After 20 years in hospitals, clinics, courts, and schools, including Boston Children’s Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Dr. Jackman created InnoPysch because she saw the importance of people of color having a therapist who looked like them (17).

- Make room at the table: Wayside Youth and Family Support Network commitment to diversity and inclusion and continued investment in the development of their POC staff have not only reduced turnover of staff of color but increased managers of color from 27% to 35% (18).

We know COVID-19 will increase traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and substance use. We know traditionally, mental health service utilization will be disproportionally lower for people of color. If we want to see different outcomes, we need to start with different inputs. As a region, we cannot be complicit - we need dedicated thought and intentional actions to close the gaps in mental health inequality.

This issue of Equity Matters was prepared by Katherine Ponce, a Fellow in the Sillerman Center for the Advancement of Philanthropy at the Heller School at Brandeis University. She can be reached at Intern@mwhealth.org

(1) Mauch, Ph.D., D., & Sharp, MPP, C. (2020). Estimated COVID-19 Behavioral Health Outcomes: Research in Perspective to Inform Action to Mitigate Morbidity and Mortality. Massachusetts Association for Mental Health.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Fry, R., & Parker, K. (2018, November 15). ‘Post-Millennial’ Generation On Track To Be Most Diverse, Best-Educated | Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/11/15/early- benchmarks-show-post-millennials-on-track-to-be-most-diverse-best-educated-generation-yet/

(4) Gallo, R. (2019). Building Inclusive Communities. MetroWest Health Foundation, 28.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Garland, Ph.D., A. F., Lau, Ph.D., A. S., Yeh, Ph.D., M., McCabe Ph.D., K., Hough Ph.D., R. L., & Landesverk Ph.D., J. A. (2005). Racial and Ethnic Differences in Utilization of Mental Health Services Among High-Risk Youths. Am J Psychiatry, 162(7).

(7) Lagomasino, I. T., Dwight-Johnson, M., Miranda, J., Zhang, L., Liao, D., Duan, N., & Wells, K. B. (2005). Disparities in Depression Treatment for Latinos and Site of Care. Psychiatric Services, 56(12), 1517–1523. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517

(8) Henderson, Z. (2017). In Their Own Words: How Black Teens Define Trauma. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12(1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0168-6

(9) 2006-2020 Adolescent Health Equity and Health Disparities in the MetroWest Region. (2020). MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey.

(10) CWS Data Tool: Demographics of the U.S. Psychology Workforce. (2018, October). Https://Www.Apa.Org. https://www.apa.org/workforce/data-tools/demographics

(11) 2017 U.S. Medical School Faculty. (2017). AAMC. Retrieved June 22, 2020, from https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/interactive-data/2017-us-medical-school-faculty

(12) “‘Post-Millennial’ Generation On Track To Be Most Diverse, Best-Educated” (above)

(13) Ibid.